North Windows, on the Chancel

View of the North Windows, from west to east. The north windows contain imagery related to the Old Testament. Descriptions here go from top to botton, left to right.

Noah, holding the Ark (not to scale). The biblical account of Noah is familiar to anyone who spent any time in Sunday School classes (perhaps with felt boards of paired animals). As detailed in Genesis 5-9. The overwhelming sinfulness of humanity has led God to “regret” having created people, and so he intends to wipe the slate clean with a flood. But Noah has found favor with God, and so is selected to gather his family and two of each animal to be spared on an ark. After the floodwaters subside, God gives the symbol of a rainbow as an assurance that God will never again send a flood to destroy the world.

The original Noah window contained the rainbow image and the dove with an olive branch (the sign God sent to let Noah’s family know that the waters were beginning to retreat), but these symbols are now at the rear of the sanctuary.

The symbol next to Noah’s head presents a bit of a mystery. The original pamphlet about the windows describes this with: “Rayed Equilateral Triangles represent God the Father and Creator.” There are two curiosities with this description: first, the phrase “rayed (equilateral) triangle” almost always refers to a common Freemason symbol. And second, equilateral triangles in Christian art typically represent the Trinity (three co-equal Persons)—not specifically “God the Father and Creator.” (See, for instance, the image of St. Athanasius holding an equilateral triangle). One possibility here, given the original placement of this symbol on a window with images from the opening chapters of Genesis, is that the equilateral triangle represents the trinitarian character of the creation event (that is, creation is attributed not to the Father alone, but to the preincarnate Word and the Spirit sweeping over the primordial waters as well), with the rays depicting something like the Big Bang/ “And there was light” moment.

Spade and Distaff, representing Adam and Eve and the curse of toil that was part of the consequences of their having disobeyed God

(“…cursed is the ground because of you; in toil you shall eat of it all the days of your life; thorns and thistles it shall bring forth for you; and you shall eat the plants of the field…” Genesis 3:17b-18a). A distaff is used in spinning and making fabric, and—even though the Genesis curse focuses on the difficulty of cultivating food crops— the distaff has often been used in art depicting Eve doing traditionally female labor. Here is a 12th-13th-century Sicilian mosaic showing Adam and Eve engaged in similar work.

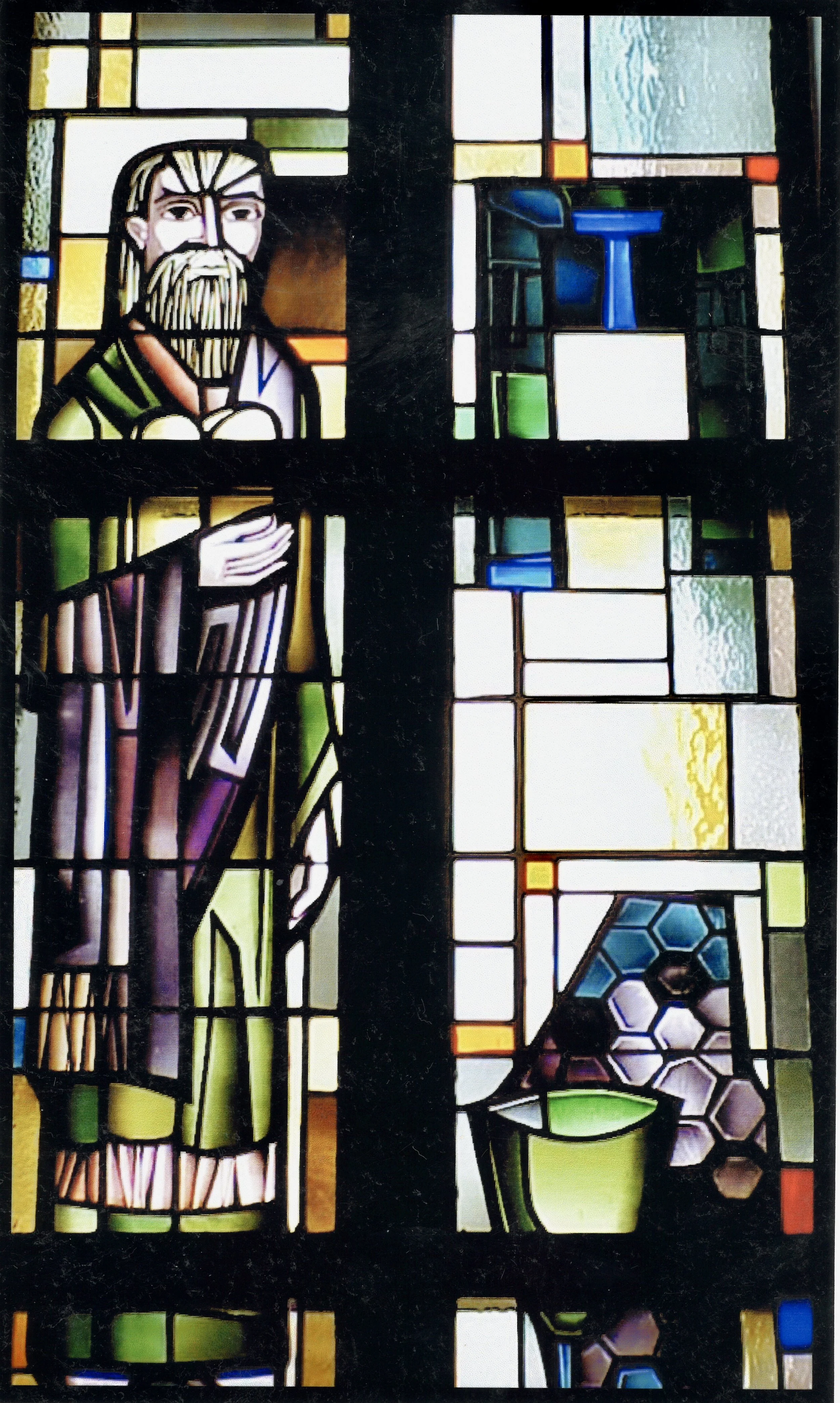

Moses, North Windows.

Moses holds two stone tablets containing the Ten Commandments (Exodus 31:18; Exodus 20:1-17). The Doorway with Crosses (upper right) represents the deliverance from bondage in Egypt. The crosses might seem anachronistic in depicting an Old Testament event, but Christians (especially in our Reformed tradition) have traditionally read Old Testament events and figures typologically (as an added layer of meaning in addition to their immediate sense), pointing forward to fulfillment in Christ. The Exodus narrative has received special Christological emphasis, with Christ leading a deeper, eternal Exodus out from sin and death.

The Vessel of Milk and Comb of Honey represent the Promised Land, which is described as “a land flowing with milk and honey” (Exodus 3:8, et al.). As with the Exodus, the Promised Land also prefigures a future reality (see, for example, Hebrews 11:13-16).

Abraham, North Windows.

Abraham holds a knife, representing his willingness to sacrifice his son Isaac when his obedience was tested by God (Genesis 22). Isaac was the child of God’s promise to Abraham and Sarah, and had been conceived and born through miraculous circumstances, so God’s instructions to Abraham represent the ultimate test of faith. While God does at the last moment provide an alternate sacrifice, sparing Isaac’s life, this account is among the most challenging and troubling in all of Scripture, and it ultimately can only begin to make sense in light of (and as a prefiguring of) the sacrifice of Christ the Divine Son on the cross.

The Bundle of Wood in the form of a Cross represents Isaac, who is a type of Christ. The cross is for us a familiar Christian symbol of salvation and redemption, but it originated as a Roman method of execution, marked by torture and humiliation—God’s transformation of this device and symbol into the means of reconciliation and salvation highlights God’s power to redeem even the most broken and sinful elements of fallen creation.

The presence of this cruciform image in this Old Testament narrative reminds us of the Christian hermeneutic (emphasized especially by our Reformed tradition) of reading the Old and New Testaments as being intrinsically connected as a pattern of promise and fulfillment.

Detail, Abraham, North Windows.

The Chalice in Christian art represents the cup used at the Last Supper, which we remember during the sacrament of Communion. In this most common Christian sense the chalice represents Christ’s “blood of the covenant, which is poured out for many” (Mark 14:24, et al.). “The cup” that Jesus drinks (Mark 10:38, et al.) also represents his redemptive suffering on our behalf, and we are told that his followers are called to share in this suffering in some way (Mark 10:39-40, et al; cf. also passages about “taking up our cross”—e.g. Matthew 10:38).

In its relation here to Abraham, it also represents Melchizedek, the King of Salem and a high priest in Abraham’s day. In an encounter in Genesis 14:18-20, Abraham tithes to and is blessed by Melchizedek, both of which are interpreted in the book of Hebrews (5:1-10) as representing a higher priesthood, which is fulfilled by Christ himself, who is “a priest forever, according to the order of Melchizedek.”

North Windows, Bottom of Tower.

The Crown, represents King David who was king over the united kingdom of Israel (the southern kingdom of Judah and the northern kingdom of Israel, c. 1000 BCE). Despite some moral failings, David is said to be a man after God’s own heart (1 Samuel 13:14), which is evidenced in his response (Psalm 51) to Nathan’s correction (2 Samuel 12) after the incident with Bathsheba and Uriah (2 Samuel 11).

Jewish messianic expectations focused on the return of a king in the Davidic line and mold (2 Samuel 7:16, Isaiah 11:1, Jeremiah 23:5-6), and this connection is amplified in the New Testament through Jesus’ genealogy (Matthew 1:1ff) and his designation as “Son of David” (e.g. Matthew 21:9).

The Fiery Chariot (you are forgiven if you didn’t recognize this image as a chariot) represents the Prophet Elijah. In 2 Kings 2:11 "...there appeared a chariot of fire...and Elijah went up by a whirlwind into heaven." This account of the prophet’s departure led to the common belief that Elijah did not die before entering heaven, and this belief is connected to Malachi’s prophecy (Mal. 4:5-6) that God “will send you the prophet Elijah before the great and terrible day of the Lord comes. He will turn the hearts of parents to their children and the hearts of children to their parents, so that I will not come and strike the land with a curse.”

Jesus and the angel Gabriel teach (Matthew 11:14, Luke 1:17) that this prophecy was fulfilled in John the Baptist, whose life paralleled Elijah’s in various ways.

The prophet Isaiah, who predicted the coming of Christ, holds tongs and a burning coal. This image derives from Isaiah 6:6ff, where—as part of Isaiah’s commissioning to preach—an angel in a vision touches a burning coal to his lips, purifying him and filling his speech with divine power. Isaiah responds to this purification by answering God’s call with his famous words, “Here I am; send me!”

The Scroll represents the prophet Ezekiel, whose prophetic call came through the symbolic act of eating a scroll (Ezekiel 3:1ff). There, the “likeness of the glory of the Lord” appears to Ezekiel in a vision and instructs him: “Eat this scroll, and go, speak to the house of Israel.” Ezekiel complies and describes the taste of the scroll as being “as sweet as honey.”

Thus, in this window we have two different symbolic representations of God putting his words into the mouths of prophets—one by purifying the lips, and the other by literally consuming God’s words.

The Cistern represents the prophet Jeremiah. A cistern is a reservoir for holding or collecting water. Empty cisterns were sometimes used as prisons, and Jeremiah was thrown into one (Jeremiah 38:6). Jeremiah also relayed God’s charge (Jeremiah 2:13) that God’s “people have committed two evils: they have forsaken me, the fountain of living water, and dug out cisterns for themselves, cracked cisterns that can hold no water.” Thus, the cistern can also represent our attempts to store up blessings for ourselves, rather than trusting in God to provide for us our “daily bread.” This reminds us that the deepest blessing comes not from God’s provision itself, but from our connection to God as we continually receive God’s gifts with gratitude.